KULM, N.D. — Excuse him, but Ed Melroe wants to say a discouraging word about … cattle.

Actually, it’s cow-calf economics that put a burr under his saddle.

Melroe, 70, is proud of the art and science of cattle breeding and the miracle of bringing calves into the world. But he has a deep concern that cow-calf producers have been losing too much money for too long: “If the cow-calf producer isn’t successful, where are the calves going to come from that are going to be fed for our table?”

Mikkel Pates / Agweek

Melroe said most cow-calf ranches, including his Sunnyside Ranch, recently reduced to a 40-cow operation, haven’t seen a clear profit since 2016 .

"When we were at the top, and we were making some money, we were paying some of the old loans, the old notes, the old debts," he said.

ADVERTISEMENT

Melroe acknowledges it’s not easy to count pluses and minuses in cattle. Shifts often are hidden in equity and condition of cattle and machinery. Sometimes lenders will make operating loans if there are assets to secure it.

Melroe is a member of R-CALF USA (Ranchers-Cattlemen Action Legal Fund United Stockgrowers of America), a national, non-profit organization. On Jan. 19, 2022, R-CALF submitted testimony to the House of Judiciary Committee's subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law. Bill Bullard, the organization’s chief executive officer, asked Congress to implement emergency help for the industry.

Bullard said that since 2015, beef packers have purchased cattle at only 55% of the average weekly wholesale beef prices, causing “horrendous losses to both cattle feeders and cow/calf producers.” Bulllard said that if packers had paid the same percentage they’d paid from 2007 to 2014, producers would have received an additional $650 per head. The group is asking for “emergency stopgap measure” of tying cattle prices to a “wholesale beef value index” to prevent the “ongoing loss of equity” suffered by cattle farmers and ranchers, and beyond that "meaningful market structure reforms.”

COOL running

Among other things, Melroe and R-CALF promote Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) which was in place from March 2009 to 2015. It required that any meat sold in the U.S. be labeled for what country it was raised in and processed in. The World Trade Organization (WTO), which includes Canada and Mexico, took legal action against COOL as anti-competitive.

”Our politicians decided to just cut that (COOL) out,” Melroe said. “That’s when things started to unravel.”

Melroe is upset that four packers together — three foreign owned — control 85% of the market. Foreign beef can be inspected by U.S. Department of Agriculture inspectors, and it receives a USDA sticker. He thinks that’s wrong.

It hurts him to hear armchair cattle experts express optimism for cattle producers when prices click upward while downplaying the rising cost of production — inputs and equipment. Melroe notes that his 145 hp tractor probably would cost $225,000 to replace.

ADVERTISEMENT

“When I buy used machinery, the cost is through the roof!” he said.

Mikkel Pates / Agweek

This is the first winter in 25 years Ed Melroe hasn’t had cattle in his yard. The drought made this year’s hay crop “very light.” The price of hay has gone from $35 to $40 a bale to roughly $150 a bale. The average cow will eat seven large round bales through the winter. Melroe said he’d like to fully retire, but in today’s economics, he can’t afford to sell the 40 head he has remaining.

Melroe’s operation peaked at about 100 cows about three years ago, including 30 registered Hereford cows. Today, Ed has trimmed back to the original 320 acres. In recent years, he’s gone commercial — breeding to Angus bulls and calving in late April. He raises first-cross “baldie" heifers and steers, which removes some of the management and breeding paperwork associated with maintaining a registered herd.

Ed took 30 of his his bred cows to Nebraska to a feedlot to over-winter. Another 10 are cared for by Ryan Wolf, a partner in nearby Wolf Farms.

Mikkel Pates / Agweek

Ryan Wolf, 39, agrees the cost-price squeeze is serious. Like Melroe, he thinks the “packers have been skinning us alive for the past five, six years.”

“They’re making record profits and we’re losing money,” Wolf said. “We’re doing the hard, physical work on the deal. Feedlots are breaking even to losing money.”

Wolf said he’s seen some friends forced out of the cattle business. He and friend, Eric Giesler, Edgeley, 35, separately went to the county Farm Service Agency office to sign up for their payments for 2021 drought relief. Giesler said the payment is $55 per animal, so based on Geisler’s 250 bred cows, the payment is about $13,500. That helps with cash flow, but it doesn’t put a big dent in the losses, Giesler and Wolf said. They’d prefer to get their money from the marketplace.

Mikkel Pates / Agweek

The Wolfs usually take cattle to 700- to 800-pounds and sell them about March 1 at Hub City Livestock Auction in Aberdeen, South Dakota. They’ll go to a feedlot and are finished to about 1,400 to 1,600 pounds.

ADVERTISEMENT

Steve Hellwig, co-owner at Hub City with brothers, Rick and Ron, said business has been more than brisk, and for difficult reasons. Hub City sold 282,000 cattle in 2021, averaging about 5,500 to 6,000 per week, year-round, with no summer lull.

“It’s a 52-week battle,” Steve acknowledges. More than half come from 100 miles to 150 miles away On Jan. 12, 2022, cattle came from as far away as Minot, North Dakota.

Mikkel Pates / Agweek

Steve said about 15% to 20% of the calves being sold “should not be sold right now,” from producers who would normally keep them another 30, 60 or 80 days and use their feed at home.

“A lot of producers don’t have the choice. They’ve gotta keep the (bred) cows at home. They’re saving the feed they have and selling the calves a lot earlier than normal,” he said.

The average calf price was was about $1,100. At 6,000 head, the total was about $6 million to $7 million, for a single sale.

“A producer (who) gets $1,200 for a calf may have $900 to $1,100 into the animal," Steve said. “He needs all of that and more just to get by.”

He said two big problems are what he calls the “Cs.” That’s COVID and corn prices. COVID hit the market, making prices plummet. Then, corn prices went to $7 per bushel. And now, inflation is causing costs to rise.

Mikkel Pates / Agweek

“We know a lot of these know these farmers personally. We’ve know them 30 years. We’ve grown up with them, we know their kids, their families," Steve said. “We’ve had a lot of kitchen talks on what do we do? Do we have to sell some cows? How do we make more money?”

Yes, the market has come up a bit, so some cattle are “slightly profitable,” Steve said. “But it seems like the good times last just a little while, and the bad times last a long while. It’s been a burden on producers to make ends meet here.”

Yes, that Melroe

Edward Hollan Melroe, has seen a lot in agriculture. He grew up in Gwinner, North Dakota, and got his name from his grandfather, the fabled Edward Gideon “E.G.” Melroe, who founded Melroe Manufacturing Co.

Mikkel Pates / Agweek

Ed’s father, Irving “Irv”, and uncles Lester, Clifford, Roger, brother-in-law Eugene (Evie) Dahl, ran the company that would become Bobcat, making skid-steer loaders. In 1969, the Melroes sold Bobcat to Clark Equipment Co. who sold to Ingersoll-Rand in 1995, who sold to Doosan Infracore in 2007.

In 1961, Irv and his wife Sylvia moved to Lisbon, where Ed graduated from Lisbon High School. Ed went to North Dakota State College of Science at Wahpeton and then “went farming” with his dad near Dwight, North Dakota.

In 1975, Ed and Irv sold the Dwight farm and moved to southeast Colorado to farm.“About the time we got 14 irrigators up, (President) Jimmy Carter slapped an embargo on Russia and wheat went to $1.76 (per bushel),” he recalled “Yah. Not good.”

The Melroes then traded the Colorado land for some Texas panhandle farmland. In 1981 Ed went to work at Boulder, Colorado, where his father and uncles started another business in Colorado making six-wheel-drive skid-steer loaders.

“Interest rates were 20%,” he said, and the business closed. Ed managed a Case-IH satellite store in Burlington, Colorado, until about 1996 when he moved back to North Dakota.

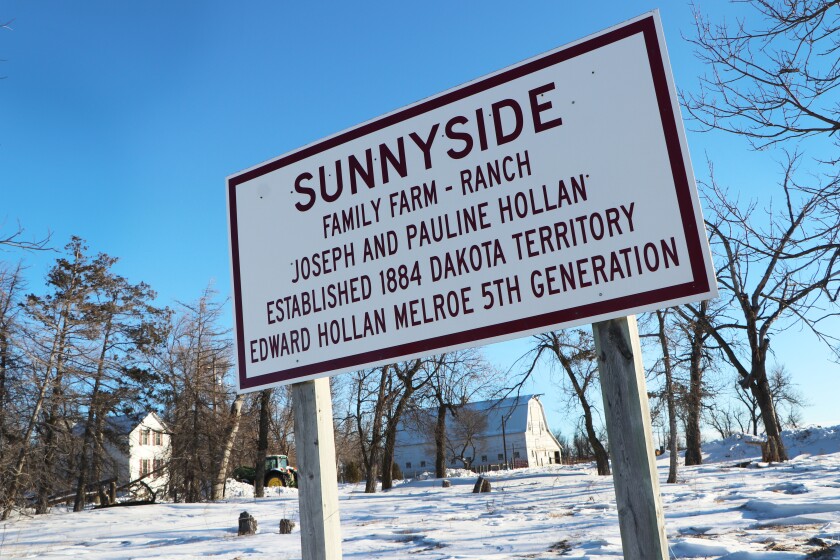

Ed joined his mother, Sylvia and step-father, Winston “Win” Stothert, at Sunnyside Ranch, south of Kulm, North Dakota. The farm had been homesteaded by Ed's great-grandfather, Joseph Hollan, in 1884, and Sylvia and her husband purchased it from her brother. Ed’s son, Michael, works at Bobcat, but helps on the ranch today.

Ed keeps a billboard in front of the Sunnyside Ranch, marking the history.

January 31, 2022 at 06:33PM

https://www.agweek.com/business/theres-little-or-no-cow-calf-profit-in-the-real-world

There's little or no cow-calf profit in the 'real world' - AG Week

https://news.google.com/search?q=little&hl=en-US&gl=US&ceid=US:en

No comments:

Post a Comment