Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

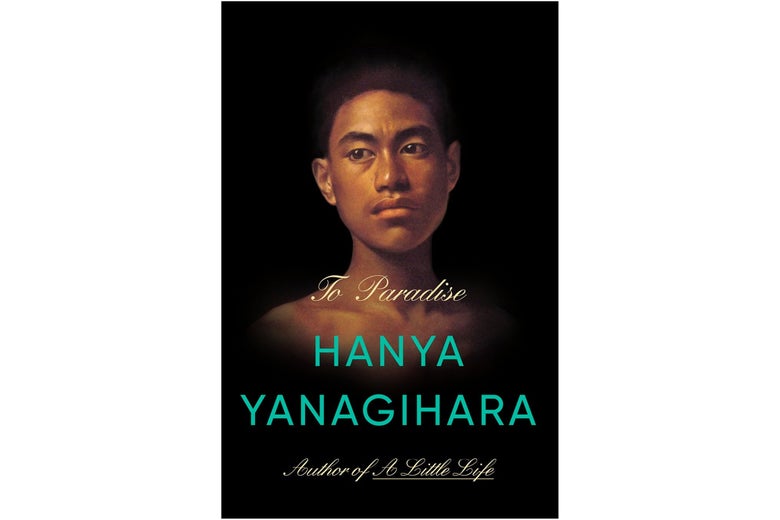

The first question most readers will have about Hanya Yanagihara’s new novel, To Paradise, is whether it replicates the appeal of her surprise bestseller, 2015’s A Little Life. The answer is no, or not much. A polarizing doorstop that begins as a four-college-friends-in-New-York soap opera and resolves into a saga of the elaborate physical, sexual, and emotional mortifications of a character named Jude St. Francis, A Little Life has a cloistered, obsessive quality reminiscent of fanfiction. It is that rare product of a complex, acutely private fantasy life that successfully communicates the intensity of that life on the page. Reading it, I was often reminded of a fanfiction subgenre known as “hurt/comfort,” in which the sufferings of one character provide a cathartic emotional payoff when that character’s beloved rushes to console him, as Willem does for Jude over and over again in A Little Life.

The fetishistic aspect of this scenario means that it enthralls some readers while putting others off, sometimes to the point of moral indignation. But literature is full of fetishistic charms of one kind or another. That’s one of the things that makes it pleasurable, and we all have our own preferences. With hurt/comfort, the thrill isn’t (typically) sadistic. It’s just that the extremes of the hurt character’s wretchedness are required to pry the utmost concern, tenderness, and care from the comforting character, closing the circle and affirming their love. That’s what makes it a story, because the erotics of hurt/comfort is an erotics of narrative, not pain.

With To Paradise, Yanagihara toys, dominatrix-style, with her readers’ desire for narrative fulfillment. The novel consists of three “books,” each almost the length of the average novel, the first and third of which set up considerable suspense about what will happen to their central characters and then refuse to resolve it. All three parts are inspired, to varying degrees, by the short Henry James novel Washington Square. This is most obvious in the first part, which is set, like Washington Square, in New York City in the late 1800s. To Paradise’s alternate version of the city, however, belongs to a political entity called the Free States, where same-sex marriage is commonplace and women pursue the same professions as men. Other parts of the North American continent, which has fractured into different nations, are not so enlightened.

Like Washington Square, To Paradise is essentially about class. For David Bingham, the central character of the 19th century portion of the novel, his family’s wealth and status are both a fortress and a prison. The Binghams don’t just have money, they have old money, and arranged marriages within their set aren’t remarkable. Unlike his enterprising married siblings, David is adrift and psychologically fragile. David, along with the grandfather who raised him after his parents’ deaths, refers to his “confinements,” which sound like the down swings of bipolar disorder. David is safe in the townhouse on Washington Square where he lives with his grandfather, but he’s sequestered from life’s rewards as well as its risks. Until, that is, he meets Edward, a charming bohemian music teacher, with whom he falls in love. Edward invites David to join him in starting a silk farm in California, but David’s grandfather, who has found evidence that Edward is a fortune hunter, threatens to disinherit David if he accepts. To complicate matters, the two men will have to conceal their relationship on the West Coast, where homosexuality is illegal.

Despite some clumsy and anachronistic language, this is the most engaging of To Paradise’s three parts, and it’s with a frustrating wrench that the reader submits to the transition to Book II, set in the 1980s during the AIDS crisis. Book III is set in the mid- and late-21st century, when America has been reduced to a totalitarian dystopia after a series of pandemics. Throughout, the Washington Square house serves as a refuge, provided by a loving older figure, that nevertheless divides a younger, protected person from some essential vitality. Characters named David, Edward, and Charles (an adoring older suitor rejected by the David Bingham in Book I) recur in ever-shifting patterns. In Book II, David is a younger native Hawaiian living in New York with his older lover, Charles, mourning his father, also named David, who fell, disastrously, under the spell of a radical Hawaiian nationalist named Edward. Both of these Davids are descendants of the Hawaiian royal family deposed by Western colonists, rich and privileged among their own people, but also trapped in an obsolete identity. In Book III, a Hawaiian epidemiologist named Charles accepts a prestigious job in New York that will eventually destroy him, as he oversees the setting-up of containment camps for the infected.

This kaleidoscope of Davids, Edwards, and Charleses is bookended by two stories of people who must decide between security and uncertainty, whether to stay home or to strike out for the unknown. Yanagihara evidently disdains simplistic imperatives. Maybe the ambitious epidemiologist should have stayed in Hawaii, where he would have died in a pandemic but not ended up with blood on his hands, and maybe the Hawaiian prince should have left the islands where he “knew that what I was would always be more significant than who I was—indeed, what I was was the only thing that made who I was significant at all.” This choice feels most sharply drawn for the novel’s original David, left poised between Washington Square and what sounds like a pretty bad bet in the original Edward, but convinced that, “This was happiness, this was life,” when in his lover’s arms.

The novel ends with Charlie, the granddaughter of the epidemiologist, similarly mid-adventure. As a child, she survived “the illness” thanks to a drug that changed her physically and mentally, scarring her skin and subduing her emotions and spirit. Even as her grandfather mourns this loss, he wonders if it might actually be a blessing, that perhaps “her affectlessness is a kind of stolidity,” or that she’s “evolved and become the sort of person who’s better-suited for our time and our place.” The future New York of Book III is an unrelentingly grim place, where food and water are rationed and books and TV are prohibited. In this world, no one would want to feel more than a drone does, especially when, Charlie’s grandfather reflects, “If we have lived, it is because we are worse than we ever believed ourselves to be, not better. … We are the left-behind, the dregs, the rats fighting for bits of rotten food, the people who chose to stay on earth, while those better and smarter than we are have left.”

But Charlie is offered an out. Will she make it? It’s only fair to warn potential readers of To Paradise that, as with the original David’s fate, they will never know. Yanagihara will even taunt them about it. Charlie listens to a storyteller recounting a tale “about a man who had lived here, on this very island, on this very Square, 200 years ago, and who had forsaken great riches from his family to follow the person he loved all the way to California, a person who his family was certain would betray him,” but the storyteller is arrested by the authorities, leaving her to wonder for years afterwards what happened. It’s to Yanagihara’s credit that To Paradise kindles such desire in its readers, even if the novel is too rangy and diverse to satisfy the hurt/comfort fans who adored A Little Life. To leave that desire unsatisfied, however, seems imperious and even a bit cruel. Seven hundred and twenty pages makes for a very long tease.

January 13, 2022 at 05:58AM

https://slate.com/culture/2022/01/paradise-hanya-yanagihara-book-review-little-life.html

To Paradise review: Hanya Yanagihara's followup to A Little Life is a lot of disappointment. - Slate

https://news.google.com/search?q=little&hl=en-US&gl=US&ceid=US:en

No comments:

Post a Comment