On the outskirts of the north-eastern French city of Reims, winding roads converge near a gated chateau. Cars line a roundabout enclosed by sprawling fields. The air is still, and it's calm. The real action is happening almost 20m underground.

Carving through this underworld are more than 200km of cellars, with millions of Champagne bottles lining chalky rock walls, unlabelled and marked with the words "I was here" by tourists in the dust covering them. Some are upside-down, in chains, glowing in the dim light of the cellars against the backdrop of tunnels that seemingly lead to nowhere. Others are stacked in small caves guarded by wrought iron gates. This is ground zero of the world's Champagne market.

And, historically in the caves, widows ruled.

Some of the biggest innovations of Champagne came down to the ingenuity of several women. In the 19th Century, the Napoleonic Code restricted women from owning businesses in France without permission from a husband or father. However, widows were exempt from the rule, creating a loophole for Barbe-Nicole Clicquot-Ponsardin, Louise Pommery and Lily Bollinger – among others – to turn vineyards into empires and ultimately transform the Champagne industry, permanently changing how it's made and marketed.

In 1798, Barbe-Nicole Ponsardin married François Clicquot, who then ran his family's small textile and wine business, originally called Clicquot-Muiron et Fils in Reims. It turned into a financial disaster. When Clicquot died in 1805, leaving her widowed at 27 years old, she made the unconventional choice to take over the company.

"It was a very unusual decision for a woman of her class," said Tilar Mazzeo, cultural historian and author of The Widow Clicquot. "It would have been extremely unusual for her to have a business, because she didn't need to… She could have spent her life in drawing rooms and as a society hostess."

In Reims, old Champagne bottles are stacked in an underworld of more than 200km of cellars (Credit: Lily Radziemski)

Desperately in need of money for the business, she asked her father-in-law for today's equivalent of about €835,000.

"Amazingly, her father-in-law said yes," Mazzeo explained, "which I always think must say something really important about who he thought she was, and what he thought she was capable of as a woman with no business background."

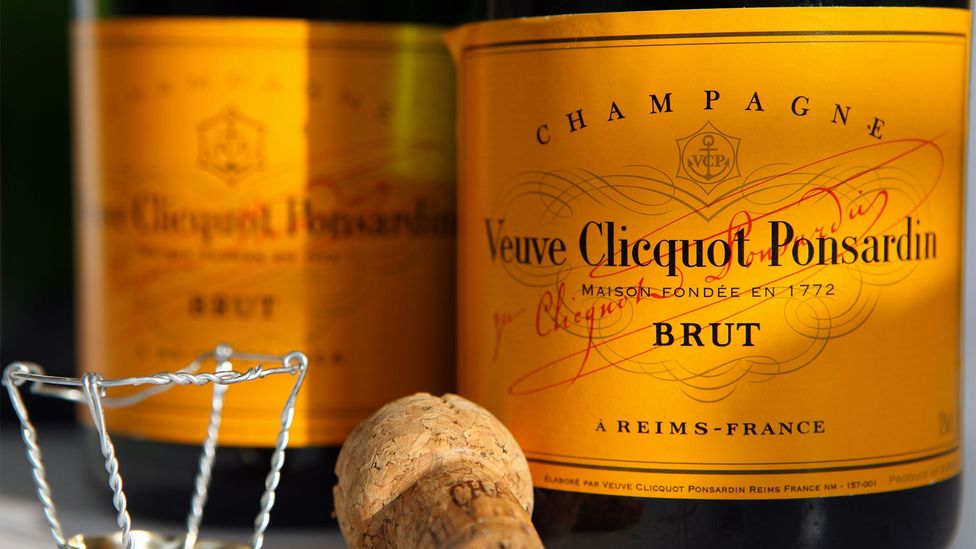

From the beginning, Barbe-Nicole used her widowed status as a marketing tool, yielding positive results. The Champagne house became Veuve Clicquot-Ponsardin – the French word veuve translates into "widow".

"The 'veuve' suggested a certain kind of respectability to the beverage… some of these beverages had gotten associated with the debauchery and wild parties of the royal courts of old," explained Kolleen M Guy, author of When Champagne Became French: Wine and the Making of a National Identity and chair, Division of Arts and Humanities at Duke Kunshan University in Jiansu, China.

Barbe-Nicole Ponsardin took over what became Veuve Clicquot-Ponsardin when her husband passed (Credit: INTERFOTO/Alamy)

Tagging "veuve" onto a bottle brought clout, and other Champagne producers – such as Veuve Binet and Veuve Loche – soon followed suit.

"The companies that didn't have a widow at the head of the household would create kind of off-brands, like a veuve off-brand, so they could try to capture this trend," Guy said.

Despite Barbe-Nicole completing a four-year apprenticeship with a local winemaker to better learn how to make the business grow, it was once again on the brink of collapse in the early 19th Century. She secured another €835,000 from her father-in-law to salvage it. However, doing this during the Napoleonic Wars in continental Europe wouldn't be easy, as border closures made it difficult to move product around.

But by 1814, Barbe-Nicole knew that she was running out of options. Faced with bankruptcy, she turned to a new market: Russia. While Russia's border was still closed towards the end of the Napoleonic wars, she decided to run the blockade.

Adding "veuve" (meaning "widow") onto a Champagne bottle such as Veuve Clicquot-Ponsardin brought clout (Credit: Lynne Sutherland/Alamy)

"She made this huge gamble, where she knew that if she could get her product into Russia before Jean-Remy Moët, who was her arch-rival, she would be able to capture some market share," Mazzeo said. "Otherwise, once the border was legally open, Moët's Champagne was going to arrive, and Moët would continue to be the dominant player in that very important Russian export market."

So, Barbe-Nicole smuggled thousands of bottles across the border. The risks were high as it was late in the season and the heat could ruin the Champagne. And if caught, the bottles would be confiscated, contributing to more financial ruin. Fortunately, the Champagne arrived in perfect condition and took the market by storm.

"In 90 days, she went from being an unknown player [in Russia] to being 'The Widow'," Mazzeo said.

With the demand came a need to increase production fast. The process of removing dead yeast cells from the bottom of bottles – a necessary step in Champagne-making following the aging and fermentation process – was tedious and damaging to the quality. But Barbe-Nicole had a better idea.

"She basically said to her winemakers, 'take my kitchen table down to the cellar – I want you to poke some holes in it and let's just turn these [bottles] upside-down. Don't you think that would be a better way of getting the yeast out? The yeast would settle in the neck of the bottle, we could pop it out, that would be faster, wouldn't it?'," Mazzeo recounted. "Everybody said 'no, no no, we can't do it that way'." But they acquiesced.

That technique known as "riddling" is still a critical part of the Champagne-making process today (Credit: David Freund/Getty Images)

It worked. That technique is became known as "riddling" (to make holes in something) and is still a critical part of the Champagne-making process today.

The second widow to revolutionise the industry was Louise Pommery. Born in 1819, Pommery entered into the Champagne scene towards the end of Clicquot's life. When she was young, her mother sent her to school in England – an unusual move that would later play to her advantage.

"She wasn't just taught how to sew," said Prince Alain de Polignac, the great-great-grandson of Louise Pommery. "[Her mother] gave her an education, which was unusual for a bourgeoise girl of that time."

After her studies, she married Alexandre Pommery, who partnered with Narcisse Greno in 1856 to build up his existing Champagne house, creating Pommery et Greno. In 1858, Alexandre died. For Louise Pommery, the next move was clear. Eight days after his death, she stepped in to take over.

"Destiny swooped in, and Madame Pommery was ready," said de Polignac. "She had a 15-year-old son and a baby in her arms, and instead of returning to her mother's home, she decided to take [the Champagne house] over."

Prince Alain de Polignac looks at a portrait of Louise Pommery (Credit: Lily Radziemski)

While Clicquot might have captured Russia, Pommery was determined to own the English market.

At the time, Champagne was painfully sweet – some bottles would have up to 300g of residual sugar compared to the more typical 12 or so grams today – and it was served over ice, sort of like a slushie. As such, the English, who typically had a drier palette, didn't have a taste for it. But Pommery felt that she could make a Champagne that would get them hooked.

Her brut Champagne hit markets in 1874. The style was distinctively dry, fresh and lively. It was perfectly balanced with a light-hearted nose, delicate but assertive.

"The idea was to make a wine that was a lot more fine, with assemblage a lot more subtle, a much longer time in cave…" de Polignac said. "This exploded on the English market, because that's what they were waiting for."

Champagne tourism arose under the guise of the widows. Whereas most Champagne-makers built chateaux after achieving success in business, Pommery did the opposite, building an estate as a means of attracting success.

After the death of Louise Pommery in the mid-20th Century, Lily Bollinger emerged on the scene.

She took over the Bollinger Champagne house in 1941 when Jacques Bollinger, her husband and the owner of the brand, passed. At the time, women's rights to business ownership were still restricted (it wasn't until 1965 that women were granted full rights to employment, banking and asset management without permission) though widows were still able to circumvent the rules.

Champagne tourism arose under the guise of the widows (pictured: Champagne House of Veuve Clicquot) (Credit: Hemis/Alamy)

"She decided to take over the management – she could have sold the business," explained her great nephew, Etienne Bizot.

Bollinger brought her Champagne to the US. For three months, she travelled all over the country carting around her wines, alone. According to Bollinger's official history, she gained such popularity that she was named "the first lady of France" by the Chicago American newspaper in 1961.

A few years later, Bollinger released the R.D. (recently disgorged) vintage Champagne, a technique that she innovated by aging the bottle with its lees, the dead yeast and grape skins, for extended periods of time and then removing the sediment from the bottle by hand. The Champagne is still one of the brand's most coveted cuvees today.

"I think what's unusual about the widows is that they [don't] remarry," Guy explained. "In a way, I think they didn't do it because had they remarried, they would have had to turn over some of the business to their husbands… They'd lose their legal status, so in some ways, it was a way to keep their independence."

The independence and creativity of the three widows paved the way for generations of women to come, and their innovations are immortalised in glass bottles.

"This group of women really changed something – they were pioneers that were very engaged in the key moments [of Champagne-making], and that importance is still represented," said Mélanie Tarlant, a twelfth-generation winemaker and member of La Transmission, Femmes en Champagne, a women-led association for Champagne-makers. She makes non-dosé (low sugar-dosed) Champagne, noting that Pommery was the first to pioneer the technique that she still uses today.

"It could have been lost in time."

BBC.com's World's Table "smashes the kitchen ceiling" by changing the way the world thinks about food, through the past, present and future.

---

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

March 02, 2023 at 03:33AM

https://news.google.com/rss/articles/CBMiUWh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmJiYy5jb20vdHJhdmVsL2FydGljbGUvMjAyMzAzMDEtdGhlLWxpdHRsZS1rbm93bi1oaXN0b3J5LW9mLWNoYW1wYWduZdIBAA?oc=5

The little-known history of Champagne - BBC

https://news.google.com/search?q=little&hl=en-US&gl=US&ceid=US:en

No comments:

Post a Comment